THE SOCIETY OF JESUS (JESUITS) AND THE SPANISH INQUISITION

THE ORIGINS AND FOUNDING OF THE ROMAN PAPACY

On October 10, 366, a man named Damasus was elected Bishop of Rome. He was an energetic man who fought for the pontificate against his opponent Ursinus, another bishop elected by a small number of followers (see “Damasus I,” 1997, 3:865-866). During his pontificate, Damasus fought to confirm his position in the Church of Rome. He also fought to compel the other cities to recognize the supremacy of the Bishop of Rome over all other bishops. Damasus even went as far as to assert that the “Church of Rome was supreme over all others, not because of what the council [of Rome in 369 and of Antioch in 378—MP] decided, but rather because Jesus placed Peter above the rest, elevating him as the cornerstone of the church itself” (“Saint Damasus,” 2005).

In spite of Damasus’ efforts to establish the preeminence of Rome and his pontificate, he did not finish his work. After his death in December 384, Siricius was elected as the Pontiff of Rome. He was less educated than Damasus, but empowered himself with a higher level of authority than other bishops had demanded. Siricius claimed inherent authority without consideration of the Scriptures. He demanded, and threatened others, in order to gain more and more power. He was the first to refer to himself as Peter’s heir (see Merdinger, 1997, p. 26). Siricius died on November 26, 399. Without a doubt, he and Damasus were principal forces behind the development of a universal ecclesiastical hierarchy.

In 440, Leo I became the pontiff. He was an ardent defender of the supremacy of the Roman bishop over the bishops in the East. In a declaration to the Bishop of Constantinople, he stated:

Constantinople has its own glory and by the mercy of God has become the seat of the empire. But secular matters are based on one thing, and ecclesiastical matters on another. Nothing will stand which is not built on the Rock which the Lord laid in the foundation…. Your city is royal but you cannot make it Apostolic (quoted in Mattox, 1961, pp. 139-140).

The supremacy referred to by Leo I was based on the assumption that the Lord exalted Rome, including its church and pontiff, over other major cities because of traditions about Peter. By that time it was accepted as “fact” that Peter had been the first Bishop of Rome and that he had been martyred there. Those traditions, along with Rome’s legacy as an evangelistic influence in the first century, gave the city a “divine aura” that supposedly connected it to the apostolic age and distinguished it from other cities. These beliefs greatly influenced the development of a hierarchy in the church.

On September 13, 590, Gregory the Great was named Bishop of Rome. He was another advocate of Petrine tradition, and named himself “Pope” and the “Head of the Universal Church.” By the end of his pontificate, the theory of Peter’s primacy and that of the Bishop of Rome was firmly established. Finally, with the appearance of Boniface III on the papal throne on February 19, 607, Roman papacy became universally accepted. Boniface III lived only a few months after his election. Many other bishops followed his legacy of “runners for supremacy.”

During the Early Church, the bishops of Rome enjoyed no temporal power until the time of Constantine. After the Fall of the Western Roman Empire (the "Middle Ages", about 476), the papacy was influenced by the temporal rulers of the surrounding Italian Peninsula; these periods are known as the Ostrogothic Papacy, Byzantine Papacy, and Frankish Papacy. Over time, the papacy consolidated its territorial claims to a portion of the peninsula known as the Papal States. Thereafter, the role of neighboring sovereigns was replaced by powerful Roman families during the saeculum obscurum, the Crescentii era, and the Tusculan Papacy.

From 1048 to 1257, the papacy experienced increasing conflict with the leaders and churches of the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire). Conflict with the latter culminated in the East–West Schism, dividing the Western Church and Eastern Church. From 1257–1377, the pope, though the bishop of Rome, resided in Viterbo, Orvieto, and Perugia, and lastly Avignon. The return of the popes to Rome after the Avignon Papacy was followed by the Western Schism: the division of the Western Church between two and, for a time, three competing papal claimants.

Leo, one of only two popes accorded the appellation “the Great,” played a pivotal role in the early history of the papacy. Assuming the title pontifex maximus, or chief priest, he made an important distinction between the person of the pope and his office, maintaining that the office assumed the full power bestowed on Peter. Although the Council of Chalcedon—called and largely directed by the Eastern emperor Marcian in 451—accorded the patriarch of Constantinople the same primacy in the East that the bishop of Rome held in the West, it acknowledged that Leo I spoke with the voice of Peter on matters of dogma, thus encouraging papal primacy. The link between Peter and the office of the bishop of Rome was stressed by Pope Gelasius I (492–496), who was the first pope to be referred to as the “vicar of Christ.” In his “theory of the two swords,” Gelasius articulated a dualistic power structure, insisting that the pope embodied spiritual power while the emperor embodied temporal power. This position, which was supported by Pope Pelagius I (556–561), became an important part of medieval ecclesiology and political theory.

Little by little, at first in stealth and silence, and then more openly as it increased in strength and gained control of the minds of men, “the mystery of iniquity” carried forward its deceptive and blasphemous work. Almost imperceptibly the customs of heathenism found their way into the Christian church. The spirit of compromise and conformity was restrained for a time by the fierce persecutions which the church endured under paganism. But as persecution ceased, and Christianity entered the courts and palaces of kings, she laid aside the humble simplicity of Christ and His apostles for the pomp and pride of pagan priests and rulers; and in place of the requirements of God, she substituted human theories and traditions. The nominal conversion of Constantine, in the early part of the fourth century, caused great rejoicing; and the world, cloaked with a form of righteousness, walked into the church. Now the work of corruption rapidly progressed. Paganism, while appearing to be vanquished, became the conqueror. Her spirit controlled the church. Her doctrines, ceremonies, and superstitions were incorporated into the faith and worship of the professed followers of Christ. ---

In the sixth century the papacy had become firmly established. Its seat of power was fixed in the imperial city, and the bishop of Rome was declared to be the head over the entire church. Paganism had given place to the papacy. The dragon had given to the beast “his power, and his seat, and great authority.” Revelation 13:2. And now began the 1260 years of papal oppression foretold in the prophecies of Daniel and the Revelation. Daniel 7:25; Revelation 13:5-7. [3] Christians were forced to choose either to yield their integrity and accept the papal ceremonies and worship, or to wear away their lives in dungeons or suffer death by the rack, the fagot, or the headsman's ax. ---

The Bible would exalt God and place finite men in their true position; therefore its sacred truths must be concealed and suppressed. This logic was adopted by the Roman Church. For hundreds of years the circulation of the Bible was prohibited. The people were forbidden to read it or to have it in their houses, and unprincipled priests and prelates interpreted its teachings to sustain their pretensions. Thus the pope came to be almost universally acknowledged as the vicegerent of God on earth, endowed with authority over church and state.

--- In the early part of the fourth century the emperor Constantine issued a decree making Sunday a public festival throughout the Roman Empire. [2] The day of the sun was reverenced by his pagan subjects and was honored by Christians; it was the emperor's policy to unite the conflicting interests of heathenism and Christianity. He was urged to do this by the bishops of the church, who, inspired by ambition and thirst for power, perceived that if the same day was observed by both Christians and heathen, it would promote the nominal acceptance of Christianity by pagans and thus advance the power and glory of the church. But while many God-fearing Christians were gradually led to regard Sunday as possessing a degree of sacredness, they still held the true Sabbath as the holy of the Lord and observed it in obedience to the fourth commandment.

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the break of communion since 1054 between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.[1] Immediately following the beginning of the schism, it is estimated that Eastern Christianity comprised a slim majority of Christians worldwide, with the majority of remaining Christians being Western.[2] The schism was the culmination of theological and political differences which had developed during the preceding centuries between Eastern and Western Christianity.

A succession of ecclesiastical differences and theological disputes between the Greek East and Latin West preceded the formal split that occurred in 1054.[1][3][4] Prominent among these were: the procession of the Holy Spirit (Filioque), whether leavened or unleavened bread should be used in the Eucharist,[a] the bishop of Rome's claim to universal jurisdiction, and the place of the See of Constantinople in relation to the pentarchy.[8]

In 1053, the first action was taken that would lead to a formal schism: The Greek churches in southern Italy were forced to conform to Latin practices and, if any of them did not, they were forced to close.[9][10][11] In retaliation, Patriarch Michael I Cerularius of Constantinople ordered the closure of all Latin churches in Constantinople. In 1054, the papal legate sent by Leo IX travelled to Constantinople for purposes that included refusing Cerularius the title of "ecumenical patriarch" and insisting that he recognize the pope's claim to be the head of all of the churches.[1] The main purposes of the papal legation were to seek help from the Byzantine emperor, Constantine IX Monomachos, in view of the Norman conquest of southern Italy, and deal with recent attacks by Leo of Ohrid against the use of unleavened bread and other Western customs,[12] attacks that had the support of Cerularius. The historian Axel Bayer says the legation was sent in response to two letters, one from the emperor seeking assistance in arranging a common military campaign by the eastern and western empires against the Normans, and the other from Cerularius.[13] On the refusal of Cerularius to accept the demand, the leader of the legation, Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida, O.S.B., excommunicated him, and in return Cerularius excommunicated Humbert and the other legates.[1] According to Ware, "Even after 1054 friendly relations between East and West continued. The two parts of Christendom were not yet conscious of a great gulf of separation between them. … The dispute remained something of which ordinary Christians in East and West were largely unaware".[14]

-- In the course of the Fourth Crusade of 1202–1204 Latin crusaders and Venetian merchants sacked Constantinople itself (1204), looting the Church of Holy Wisdom and various other Orthodox holy sites,[222] and converting them to Latin Catholic worship. The Norman Crusaders also destroyed the Imperial Library of Constantinople.[223][224][225] Various holy artifacts from these Orthodox holy places were taken to the West. The crusaders also appointed a Latin Patriarch of Constantinople.[222] The conquest of Constantinople and the final treaty established the Latin Empire of the East and the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople (with various other Crusader states). Later some religious artifacts were sold in Europe to finance or fund the Latin Empire in Byzantium – as when Emperor Baldwin II of Constantinople (r. 1228–1261) sold the relic of the Crown of Thorns while in France trying to raise new funds to maintain his hold on Byzantium.[226] In 1261 the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos brought the Latin Empire to an end. However, the Western attack on the heart of the Byzantine Empire is seen[by whom?] as a factor that led eventually to its conquest by Ottoman Muslims in the 15th century.[citation needed] Many scholars believe that the 1204 sacking of Constantinople contributed more to the schism than the events of 1054.[227]

In northern Europe, the Teutonic Knights, after their 12th- and 13th-century successes in the Northern Crusades,[228] attempted (1240) to conquer the Eastern Orthodox Russian Republics of Pskov and Novgorod, an enterprise somewhat endorsed by Pope Gregory IX[228] (r. 1227–1241). One of the major defeats the Teutonic Knights suffered was the Battle of the Ice in 1242. Catholic Sweden also undertook several campaigns against Orthodox Novgorod. There were also conflicts between Catholic Poland and Orthodox Russia, which helped solidify the schism between East and West.

an official investigation, especially one of a political or religious nature, characterized by lack of regard for individual rights, prejudice on the part of the examiners, and recklessly cruel punishments.

any harsh, difficult, or prolonged questioning.

the act of inquiring; inquiry; research.

an investigation, or process of inquiry.

a judicial or official inquiry.

the finding of such an inquiry.

The term Inquisition is somewhat misleading in that over the centuries there have been a number of inquisitions. They have been directed against all of the groups we have looked at — Pagans and supposed Witches, dissenting sects, Cathars, Jews, Heretics, Philosophers, Freethinkers, Blasphemers, Apostates, Humanists, Pantheists, Unitarians, Deists and Atheists as well as Muslims, Hindus and members of other religions.

- The Medieval Inquisition and the Knights Templar

- The Spanish Inquisition

- The Portuguese and Goan Inquisitions

- The Roman Inquisition

In 1184 Pope Lucius III and the Emperor Frederick formulated a programme for the repression of heretics. This document, Ad abolendum, is sometimes known as the charter of the Inquisition, because it set the tone for future developments. The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 ordered all bishops to hold an annual inquisition, if there was a suspicion of heresy in their See. But these Episcopal inquisitions were found to be inadequate for the task.

Ad abolendam (lit. 'On abolition / Towards abolishing'; full title in Latin: Ad abolendam diversam haeresium pravitatem, lit. 'To abolish diverse malignant heresies') was a decretal and bull of Pope Lucius III, written at Verona and issued 4 November 1184.[1] It was issued after the Council of Verona settled some jurisdictional differences between the Papacy and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor. The document prescribes measures to uproot heresy and sparked the efforts which culminated in the Albigensian Crusade and the Inquisitions. Its chief aim was the complete abolition of Christian heresy.

The historical context for the issuing of Ad abolendam was papal reassertion of its authority in Europe following the Investiture Dispute with the Emperor, and its discovery of what has been called a 'legislative' means of doing so.[2] The Third Lateran Council of 1179 had already resolved to prevent schisms of the kind that the Investiture Dispute had created, and decretals such as Ad abolendam were intended to enforce this;[3] Fisher has suggested that it was no coincidence that the decree followed the Peace of Constance of the previous year, at which the Emperor was in effect compelled to acknowledge defeat.[4]

Ad abolendam ("On abolition" or "Towards abolishing") was a decretal and bull of Pope Lucius III, written at Verona in November 1184.[1] It was developed after the Council of Verona settled some jurisdictional differences between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. The document prescribes measures to uproot heresy and sparked the efforts which culminated in the Albigensian Crusade and the Inquisitions. Its chief aim was the complete abolition of Christian heresy.

All who, regarding the sacrament of the Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, or regarding baptism or the confession of sins, matrimony or the other ecclesiastical sacraments, do not fear to think or to teach otherwise than the most holy Roman Church teaches and observes; and in general, whomsoever the same Roman Church or individual bishops through their dioceses with the advice of the clergy or the clergy themselves, if the episcopal see is vacant, with the advice if it is necessary of neighboring bishops, shall judge as heretics, we bind with a like bond of perpetual anathema.

Pontificate: Sept. 1, 1181 (consecrated, Velletri Sept. 6, 1181) to Nov. 25, 1185; b. Hu[m]baldus Allucingoli (?), Lucca; d. Verona; cardinal deacon of Sant'Adriano (1138), promoted cardinal-priest of Sta Prassede (1141) by Innocent II, and cardinal bishop of Ostia and Velletri by Hadrian IV (1158); long thought to have been a Cistercian, but seems never to have become a monk.

One of the oldest popes, Lucius was a political man as well as a negotiator. Lucius was born around 1097, making him 84 when he ascended to the chair of Peter. Born Ubaldo Allucingoli, he was likely the son of Orlando, a member of a prominent Lucca family.

Little is known of Ubaldo’s early life. He may have been a Cistercian monk. He was first noticed by the Curia when Pope Innocent II named him a cardinal-deacon of San Adriano in late 1138. Only three years later, he was raised to cardinal-priest of Santa Prassede, where he remained until 1158. During that time, he was also a legate to France.

In early 1158, Pope Adrian IV promoted Ubaldo to cardinal-bishop of Ostia, where he remained until his papal election 23 years later. During that time, the cardinal was a legate to Sicily and the dean of cardinals during the papacy of Pope Alexander III. He was privileged to take part in the negotiations for the Treaty of Venice in 1177.

On August 30 1181, Pope Alexander III died after many years on the throne. The cardinals, many of whom were in Velletri to witness the death of the old pope, immediately voted Ubaldo the new pope. He was consecrated six days later, taking the name Lucius III

Until 1184, action to repress heresy in Italy was the affair of bishops in the areas affected. The Third Lateran Council (1179), which discussed the incidence of heresy, directed its attention to southern France. However, in 1184, Lucius III and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa met at Verona and jointly condemned the Cathars, Patarines, Humiliati, the Poor Men of Lyons and other sects. The papal bull Ad abolendam also prescribed penalties for heretical clerics and laymen and established a procedure of systematic inquisition by bishops.

It was Innocent III (1198-1216) who pressed papal action to wider limits. Innocent sent a stream of letters about heresy to archbishops, bishops, and secular rulers. He saw the basic necessity, reform of the Church, as the first requirement. Italy was not the scene of preaching missions against heresy or of a crusade, which was the case in southern France. In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council summed up and reaffirmed the pontifical legislation already in existence. In its first canon, the Council provided a statement of doctrine based on traditional professions of faith, but was amended to take account of present heresies. The third canon -- given below -- specified procedures against heretics and their accomplices and reproduced the Ad abolendam of Lucius III. Other canons touched on the issue of heresy in various ways.

Although the Council's attention was focused primarily on the situation in southern France, the legislation was equally pertinent to Italy where, by the time of Innocent's death (1216) the Church was mobilizing its forces against heresy and lacked only the papal inquisition, for which the precedents were already being established.

* * * * *

We excommunicate and anathematize every heresy raising itself up against this holy, orthodox and catholic faith which we have expounded above. We condemn all heretics, whatever names they may go under. They have different faces indeed but their tails are tied together inasmuch as they are alike in their pride. Let those condemned be handed over to the secular authorities present, or to their bailiffs, for due punishment. Clerics are first to be degraded from their orders. The goods of the condemned are to be confiscated, if they are lay persons, and if clerics they are to be applied to the churches from which they received their stipends. Those who are only found suspect of heresy are to be struck with the sword of anathema, unless they prove their innocence by an appropriate purgation, having regard to the reasons for suspicion and the character of the person. Let such persons be avoided by all until they have made adequate satisfaction. If they persist in the excommunication for a year, they are to be condemned as heretics. Let secular authorities, whatever offices they may be discharging, be advised and urged and if necessary be compelled by ecclesiastical censure, if they wish to be reputed and held to be faithful, to take publicly an oath for the defense of the faith to the effect that they will seek, in so far as they can, to expel from the lands subject to their jurisdiction all heretics designated by the church in good faith. Thus whenever anyone is promoted to spiritual or temporal authority, he shall be obliged to confirm this article with an oath. If however a temporal lord, required and instructed by the church, neglects to cleanse his territory of this heretical filth, he shall be bound with the bond of excommunication by the metropolitan and other bishops of the province. If he refuses to give satisfaction within a year, this shall be reported to the supreme pontiff so that he may then declare his vassals absolved from their fealty to him and make the land available for occupation by Catholics so that these may, after they have expelled the heretics, possess it unopposed and preserve it in the purity of the faith -- saving the right of the suzerain provided that he makes no difficulty in the matter and puts no impediment in the way. The same law is to be observed no less as regards those who do not have a suzerain.

The Albigensian Crusade or the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229; French: Croisade des albigeois, Occitan: Crosada dels albigeses) was a 20-year military campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, in southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crown and promptly took on a political aspect, resulting in not only a significant reduction in the number of practicing Cathars, but also a realignment of the County of Toulouse in Languedoc, bringing it into the sphere of the French crown, and diminishing both Languedoc's distinct regional culture and the influence of the counts of Barcelona.

The Cathars originated from an anti-materialist reform movement within the Bogomil churches of the Balkans calling for what they saw as a return to the Christian message of perfection, poverty and preaching, combined with a rejection of the physical to the point of starvation. The reforms were a reaction against the often perceived scandalous and dissolute lifestyles of the Catholic clergy in southern France. Their theology, neo-Gnostic in many ways, was basically dualist. Several of their practices, especially their belief in the inherent evil of the physical world, conflicted with the doctrines of the Incarnation of Christ and Catholic sacraments. This led to accusations of Gnosticism and attracted the ire of the Catholic establishment. They became known as the Albigensians because there were many adherents in the city of Albi and the surrounding area in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Between 1022 and 1163, the Cathars were condemned by eight local church councils, the last of which, held at Tours, declared that all Albigenses should be put into prison and have their property confiscated. The Third Lateran Council of 1179 repeated the condemnation. Innocent III's diplomatic attempts to roll back Catharism were met with little success. After the murder of his legate Pierre de Castelnau in 1208, and suspecting that Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse was responsible, Innocent III declared a crusade against the Cathars. He offered the lands of the Cathar heretics to any French nobleman willing to take up arms.

From 1209 to 1215, the Crusaders experienced great success, capturing Cathar lands and systematically crushing the movement. From 1215 to 1225, a series of revolts caused many of the lands to be regained by the Cathars. A renewed crusade resulted in the recapturing of the territory and effectively drove Catharism underground by 1244. The Albigensian Crusade had a role in the creation and institutionalization of both the Dominican Order and the Medieval Inquisition. The Dominicans promulgated the message of the Church and spread it by preaching the Church's teachings in towns and villages in order to stop the spread of alleged heresies, while the Inquisition investigated people who were accused of teaching heresies. Because of these efforts, all discernible traces of the Cathar movement were eradicated by the middle of the 14th century. Many historians consider the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars an act of genocide.[3][4

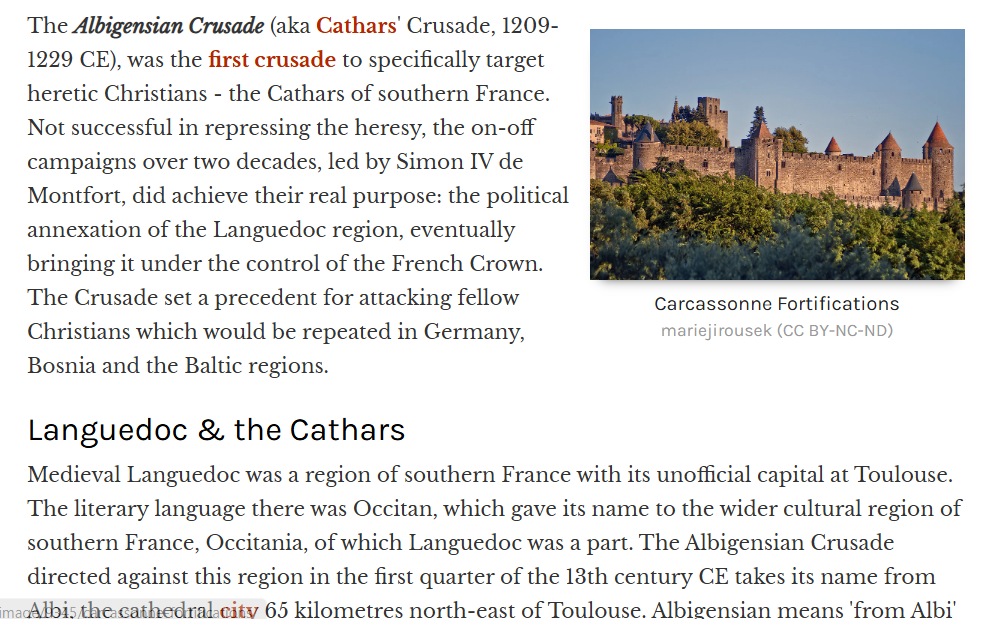

The Albigensian Crusade (aka Cathars' Crusade, 1209-1229 CE), was the first crusade to specifically target heretic Christians - the Cathars of southern France. Not successful in repressing the heresy, the on-off campaigns over two decades, led by Simon IV de Montfort, did achieve their real purpose: the political annexation of the Languedoc region, eventually bringing it under the control of the French Crown. The Crusade set a precedent for attacking fellow Christians which would be repeated in Germany, Bosnia and the Baltic regions.

Languedoc & the Cathars

Medieval Languedoc was a region of southern France with its unofficial capital at Toulouse. The literary language there was Occitan, which gave its name to the wider cultural region of southern France, Occitania, of which Languedoc was a part. The Albigensian Crusade directed against this region in the first quarter of the 13th century CE takes its name from Albi, the cathedral city 65 kilometres north-east of Toulouse. Albigensian means 'from Albi' but the heretics are more accurately known as the Cathars of Languedoc, even if their first important centre was established at Albi.

THE CATHARS, WITH THEIR OWN CHURCHES, BISHOPS & FOLLOWERS OF ALL SOCIAL CLASSES, WERE A DANGEROUS THREAT TO THE AUTHORITY OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH.

The region of Languedoc was a stronghold of the Cathars, a group of heretics who sought to promote their own ideas regarding the age-old problem of how the Christian God, a Good God, could create a material world which contained evil. Their name derives from katharos, the Greek word for 'clean' or 'pure' and they probably derived from the more moderate Bogomil heretics of Byzantine Bulgaria. The Cathars, who were also present in Lombardy, the Rhineland and Champagne regions, believed that there were two principles of Good and Evil, a dualist position that was not new and had been promoted by such groups as the 7th century CE Paulicians. The Cathars believed that an evil force (either a fallen angel - Satan - or an eternal evil god) had created the material world while God was responsible for the spiritual world. Humanity must, as a consequence of this evil, find a way to escape their material bodies and join the pure Good of the spiritual world. As the two worlds were entirely separate, the Cathars did not believe that God had appeared on earth as Jesus Christ and had been crucified.

Albigensian Crusade, Crusade (1209–29) called by Pope Innocent III against the Cathari, a dualist religious movement in southern France that the Roman Catholic Church had branded heretical. The war pitted the nobility of staunchly Catholic northern France against that of the south, where the Cathari were tolerated and even enjoyed the support of the nobles. Although the Crusade did not eliminate Catharism, it eventually enabled the French king to establish his authority over the south.

Historical background

By the middle of the 12th century, control of Jerusalem and the Holy Land was no longer the only goal of the Crusades. Rather, Crusading became a special class of war called by the pope against the enemies of the faith, who were by no means confined to the Levant. Crusades continued in the Baltic region against pagans and in Spain against Muslims. Yet in the heart of Europe a more serious threat faced Christendom: heresy, which was viewed in the medieval world not as benign religious diversity but rather as a cancerous threat to the salvation of souls. It was held to be even more dangerous than the faraway Muslims, because it harmed the body of Christ from within.

During the late 12th century and early 13th century, the most powerful and vibrant heresy in Europe was Catharism. Centered around the Languedoc region and the city of Albi in southern France, the religious movement was tolerated by the local aristocracy and allowed to thrive.

The Roman Catholic Church, wary of a center of Christian teaching over which they had limited control, had attempted for years to cut out the heresy from southern France. in this they were often thwarted by the Barons of the area such as Raymond VI of Toulouse. Things came to a head in 1208, when the Pope called a crusade against Raymond and the Cathars.

The Heresy of Mysticism

Catharism held that the universe was a battleground between good, which was spirit, and evil, which was matter. Human beings were believed to be spirits trapped in physical bodies. Their leaders lived with great austerity, remained chaste, and were vegetarian, avoiding all foods that came from sexual union.

- Joan of Arc: Divinely Inspired or Mentally Ill?

- Asherah: did the God of the Hebrew Bible have a Wife?

This abstinence was of no concern for the Catholic Church, but the teachings were more problematic. Cathar doctrines of creation had led them to rewrite the biblical story, rejecting the doctrine of the Old Testament.

Cathars believed that Jesus was merely an angel, and his human sufferings and death were an illusion. These beliefs struck at the roots of orthodox Christianity and the political power base of Christendom, and a military response from the Church looked increasingly likely as the movement grew.

Cathars grew in influence in the Languedoc throughout the twelfth century. Catholic chroniclers record that Cathars had become the majority religion in many places, and that Catholic churches were abandoned and in ruin. Of the Catholic clergy that remained some, perhaps most, were themselves Cathar believers. The Papacy responded initially be intigating preaching campaigns and engaging in public debates, both of which proved humiliating failures for the crack teams of theologians sent by the Pope.

The next response, in 1208, was a war, or more accurately a series of wars. Modern writers refer to them as the Cathar Wars, but traditionally the series was refered to as the Albigensian Crusade. It was a formal crusade in the full sense of the word - preached and directed by the papacy, and offering participants the remission of sins and an assured place in heaven. The Crusaders regarded themselves as being "on God's business" and referred to themselves as "pilgrims".

From the first major siege (at Béziers) in 1209 the War bacame one of French (+ their allies) against the independent people of the Languedoc (+ their allies). Instead of Catholics against Cathars it was, up until 1242 at least, consistently Catholics on one side against Cathars and Catholics on the other.

The war saw many sieges, including those of Béziers, Carcassonne, Bram, Lavaur, Lastours, Saissac, Minerve, Termes, Les Casses, Puivert, Toulouse, Muret, Castelnaudary, Foix, Beaucaire, Marmande, Montsegur.

These sieges were of castra, ie castles and their associated walled villages, towns or cities. Some gave up without a fight - the desired result of the Crusaders's deliberate terror tactics. These included Fanjeaux and Castelnaudary (after the fall of Béziers and Carcassonne), Lastours and Foix (both for diplomatic reasons after withstanding repeated sieges), Le Bezu and Coustaussa (after the fall of Termes), Peyrepertuse, Queribus, Puilaurens and Aguilar.

Terror tactics included mass indiscriminate slaughter as at Béziers and Marmande (and planned for Toulouse), various attrocities as at Bram and Lavaur, and mass burnings as at Minerve, Lavaur, Les casses and Montsegur.

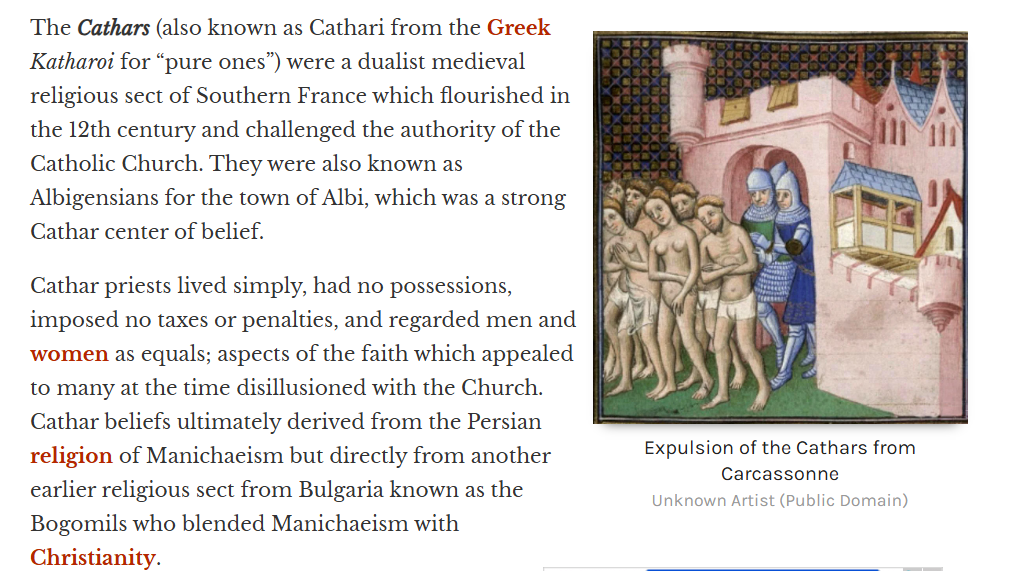

The Cathars (also known as Cathari from the Greek Katharoi for “pure ones”) were a dualist medieval religious sect of Southern France which flourished in the 12th century CE and challenged the authority of the Catholic Church. They were also known as Albigensians for the town of Albi, which was a strong Cathar center of belief. Cathar priests lived simply, had no possessions, imposed no taxes or penalties, and regarded men and women as equals; aspects of the faith which appealed to many at the time disillusioned with the Church. Cathar beliefs ultimately derived from the Persian religion of Manichaeism but directly from another earlier religious sect from Bulgaria known as the Bogomils who blended Manichaeism with Christianity.

Cathars believed that Satan had tricked a number of angels into falling from heaven and then encased them in bodies. The purpose of life was to renounce the pleasures and enticements of the world and, through repeated incarnations, make one's way back to heaven. To this end, the Cathars observed a strict hierarchy:

- Perfecti – those who had renounced the world, the priests and bishops

- Credentes – believers who still interacted with the world but worked toward renunciation

- Sympathizers – non-believers who aided and supported Cathar communities

Cathars rejected the teachings of the Catholic Church as immoral and most of the books of the Bible as inspired by Satan. They criticized the Church heavily for the hypocrisy, greed, and lechery of its clergy, and the Church's acquisition of land and wealth. Not surprisingly, the Cathars were condemned as heretical by the Catholic Church and massacred in the Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229 CE) which also devastated the towns, cities, and culture of southern France.

Origins & Beliefs

Almost everything known about the Cathars comes from confessions of “heretics” taken by Catholic clergy during the inquisition which followed the Albigensian Crusade. The belief structure can easily be traced back to Manichaeism which traveled via the Silk Road from the Byzantine Empire and the Middle East to Europe where it became entwined, under certain circumstances, with Christian belief and symbolism.

Whenever the Templars are mentioned, the Cathars are generally not far behind. Tied together with some interesting data and facts, they tend to be the focus of intense esoteric and mystical knowledge. Taking a look at them with the facts we have may answer questions, or create deeper ones.

The Cathars were the followers of a 12th to 14th C.E. Gnostic movement in Southern France and Italy. This movement, Catharism, comes from the Greek word katharoi, or “Pure Ones.” Scholars agree that the people who practiced this religion did not call themselves by this name; in all honesty, it seems unclear what they did call themselves except “The Good Christians.” The movement first took hold in the small town of Albi, in France, and the followers were also known as the Albigensians, especially to the Catholics. The ideas of Catharism were around for centuries before this larger movement took place, and possibly has its roots in what is called Paulicianism.

In the Paulicianism belief system, the adherents do not believe in the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), and in fact believe that Jesus was “adopted” by God to be his “son” and endure the necessary trials. Paulicianism was vibrant around the 7th to 9th centuries C.E., particularly in Armenia. Cathars, like the Paulicians, primarily believed in a dualistic Christian system, wherein the were two “Gods,” one good, one evil, as well as deeper Gnostic concepts. The basic tenants of the Cathar religion seem to have come from a single priest, Bogomil, during the First Bulgarian Empire in the 10th century C.E. as a response to the rise of feudalism. In other words, the oppression and slavery of Feudalistic ideas spurred this priest and his followers toward a mindset of individual freewill and worth. Like later Cathars, Bogomilism did not believe in the ecclesiastical hierarchy nor did they believe in the need for church buildings. In a sense, Bogomils, and then Cathars, were an itinerant religion, spread by men and women of the church elite – Travelers.

Most of their beliefs were radical to a still-struggling Catholic Church, and in a time prior to Luther, Catholic ideas were the only “Christian” meal to be had. The church had struggled for over a thousand years to get itself “right,” and it did not need yet one more renegade group to get in its way. Cathars believed in reincarnation of humans and animals, and did not eat the flesh of animals for this reason. They had a vibrant tradition in their troubadours, and were traveling craftsmen of many trades. Men and women were mainly seen as equals, although it is thought that their last incarnation needed to be male in order to be “close to God.” Their Good God was the creator of all that was spiritual, ethereal and thought, while the Evil God was the creator all that was material. They did not believe in hell, it being the earth in which we currently live, but heaven was populated by angels and spirits performing the will of the Good God.

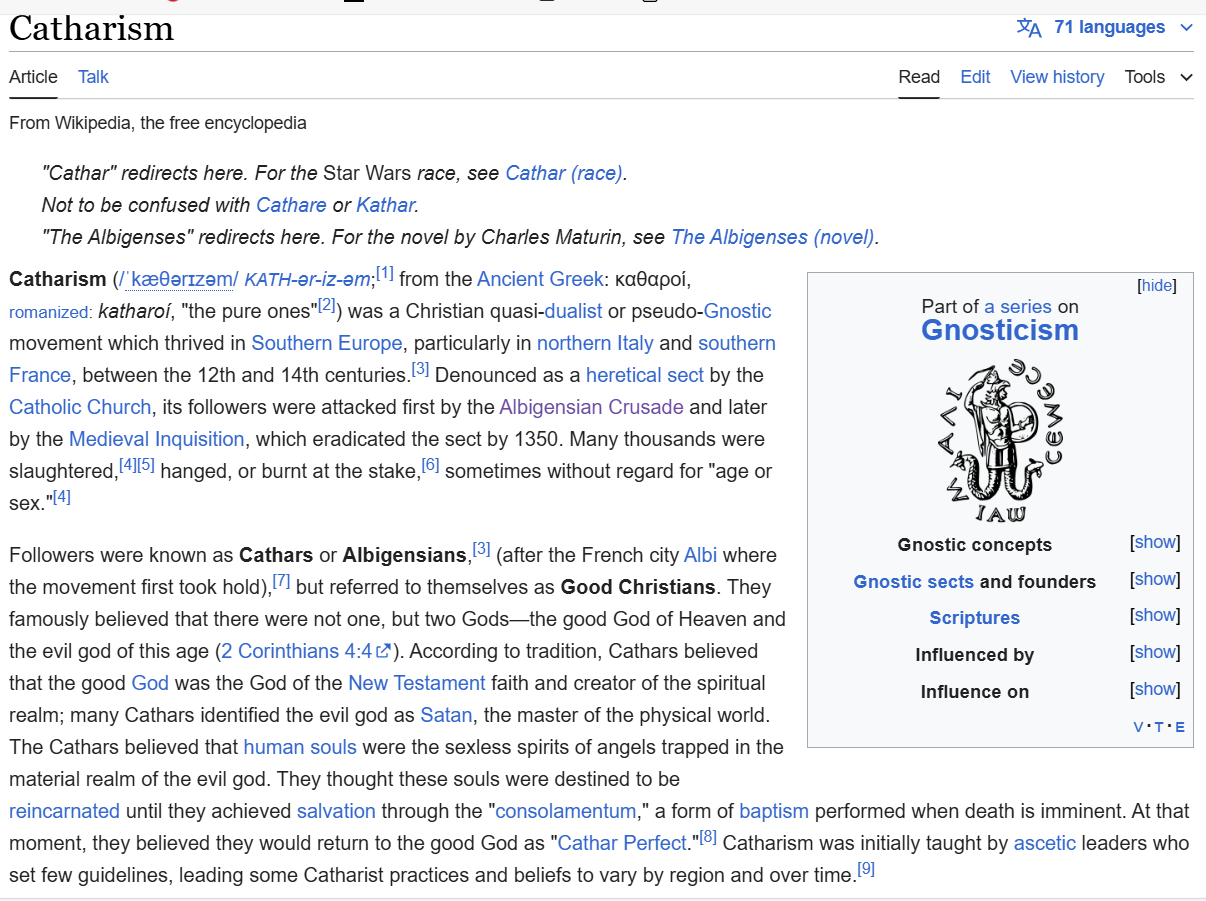

The origins of the Cathars' beliefs are unclear, but most theories agree they came from the Byzantine Empire, mostly by the trade routes and spread from the First Bulgarian Empire to the Netherlands. The name of Bulgarians (Bougres) was also applied to the Albigensians, and they maintained an association with the similar Christian movement of the Bogomils ("Friends of God") of Thrace. "That there was a substantial transmission of ritual and ideas from Bogomilism to Catharism is beyond reasonable doubt."[11] Their doctrines have numerous resemblances to those of the Bogomils and the Paulicians, who influenced them,[12] as well as the earlier Marcionites, who were found in the same areas as the Paulicians, the Manicheans and the Christian Gnostics of the first few centuries AD, although, as many scholars, most notably Mark Pegg, have pointed out, it would be erroneous to extrapolate direct, historical connections based on theoretical similarities perceived by modern scholars.

John Damascene, writing in the 8th century AD, also notes of an earlier sect called the "Cathari", in his book On Heresies, taken from the epitome provided by Epiphanius of Salamis in his Panarion. He says of them: "They absolutely reject those who marry a second time, and reject the possibility of penance [that is, forgiveness of sins after baptism]".[13] These are probably the same Cathari (actually Novations) who are mentioned in Canon 8 of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in the year 325, which states "... [I]f those called Cathari come over [to the faith], let them first make profession that they are willing to communicate [share full communion] with the twice-married, and grant pardon to those who have lapsed ..."[14]

The writings of the Cathars were mostly destroyed because of the doctrine's threat perceived by the Papacy;[15] thus, the historical record of the Cathars is derived primarily from their opponents. Cathar ideology continues to be debated, with commentators regularly accusing opposing perspectives of speculation, distortion and bias. Only a few texts of the Cathars remain, as preserved by their opponents (such as the Rituel Cathare de Lyon) which give a glimpse into the ideologies of their faith.[12] One large text has survived, The Book of Two Principles (Liber de duobus principiis),[16] which elaborates the principles of dualistic theology from the point of view of some Albanenses Cathars.[17]

It is now generally agreed by most scholars that identifiable historical Catharism did not emerge until at least 1143, when the first confirmed report of a group espousing similar beliefs is reported being active at Cologne by the cleric Eberwin of Steinfeld.[a] A landmark in the "institutional history" of the Cathars was the Council, held in 1167 at Saint-Félix-Lauragais, attended by many local figures and also by the Bogomil papa Nicetas, the Cathar bishop of (northern) France and a leader of the Cathars of Lombardy.

The Cathars were a largely local, Western European/Latin Christian phenomenon, springing up in the Rhineland cities (particularly Cologne) in the mid-12th century, northern France around the same time, and particularly the Languedoc—and the northern Italian cities in the mid-late 12th century. In the Languedoc and northern Italy, the Cathars attained their greatest popularity, surviving in the Languedoc, in much reduced form, up to around 1325 and in the Italian cities until the Inquisitions of the 14th century finally extirpated them.[18][19]

The early years of medieval Christianity greatly diverged from what we commonly associate with the teachings of Christ in the modern age. During the 11th century, an influential but ephemeral religious group known as the Cathars emerged in the Languedoc region of France.

Their dualist, Gnosticism-infused teachings confused and infuriated the Catholic church, who often could not decide whether they were Christian heretics or not Christian at all. Their beliefs are recognized as “The Great Heresy” by Roman Catholics to this day, but their official classification as Christians continues to remain ambiguous.

The Cathars obscure origins have been subject to substantial speculation; however, Persia or the Byzantine Empire were the most likely sources of influence for this medieval movement. The Cathars shared their faith and love for Christ with Christianity but departed from the doctrine in various ways.

The main difference between Christians and Cathars were two-fold;

- Cathars were Dualist, which means that they believed there were two main creative forces which governed the cosmos: A Good God, who created all souls and the immaterial heavens, and a Bad God, who created the physical world to entrap souls in flesh.

- Cathars were Gnostic, meaning they believed that the universal truth could be known only by direct experience and that only an inner elite could penetrate the esoteric knowledge by living a disciplined, pure life of asceticism.

The Cathars came from the region west-north-west of Marseilles on Golfe du Lion, the old province of Languedoc. They were a heretical sect of Christians who lived in Southern France during the 11th and 12th centuries. One branch of the Cathars became known as the Albigenses because they took their name from the local town Albi. Cathar beliefs probably developed as a consequence of traders coming from Eastern Europe, bringing teachings of the Bogomils.

Names

- Albigenses (from the town of Albi)

- Cathars (from the Greek katharos, which means "unpolluted" or "pure")

Cathar Theology

Cathar doctrines, regarded as heresies by other Christians, are generally known through attacks on them by their opponents. Cathar beliefs are thought to have included a fierce anti-clericalism and the Manichean dualism which divided the world into good and evil principles, with matter being intrinsically evil and mind or spirit being intrinsically good. As a result, the Cathars were an extreme ascetic group, cutting themselves off from others in order to retain as much purity as possible.

Gnosticism

Cathar theology was essentially Gnostic in nature. They believed that there were two "gods"—one malevolent and one good. The former was in charge of all visible and material things and was held responsible for all the atrocities in the Old Testament. The benevolent god, on the other hand, was the one the Cathars worshipped and was responsible for the message of Jesus. Accordingly, they made every effort to follow the teachings of Jesus as closely as possible.

Cathars vs. Catholicism

Cathar practices were often in direct contradiction to how the Catholic Church conducted business, especially with regards to the issues of poverty and the moral character of priests. The Cathars believed that everyone should be able to read the Bible, translating into the local language. Because of this, the Synod of Toulouse in 1229 expressly condemned such translations and even forbade lay people to own a Bible.

Treatment of the Cathars by the Catholics was atrocious. Secular rulers were used to torture and maim the heretics, and anyone who refused to do this was themselves punished. The Fourth Lateran Council, which authorized the state to punish religious dissenters, also authorized the state to confiscate all the land and property of the Cathars, resulting in a very nice incentive for state officials to do the church's bidding.

Crusade Against the Cathars

Innocent III launched a Crusade against the Cathar heretics, turning the suppression into a full military campaign. Innocent had appointed Peter of Castelnau as the papal legate responsible for organizing the Catholic opposition to the Cathars, but he was murdered by someone thought to be employed by Raymond VI, the Count of Tolouse and leader of Cathar opposition. This caused the general religious movement against the Cathars to turn into a full-fledged crusade and military campaign.

Inquisition

An Inquisition against the Cathars was instituted in 1229. When the Dominicans took over the Inquisition of the Cathars, things only got worse for them. Anyone accused of heresy had no rights, and witnesses who said favorable things about the accused were themselves sometimes accused of heresy.

The Cathars have several things in common with the Templars. They were celibate, they were accused of heresy, they were supposed to have a hidden treasure, and they were wiped out. And one thing more: they are pulled into all sorts of interesting speculations on subjects that they had nothing to do with, such as the Grail.

Who were the Cathars?

The religion contained beliefs that had been floating around for centuries, perhaps millennia. Looking at the cruelty and essential unfairness of life, some people have decided that a good god could not be responsible for such a mess. Instead of assuming that God was testing people or punishing them for their sins, these people came to the conclusion that God was not all-powerful. Some forms of this belief assumed that there must be two gods, one good and one evil, in constant battle over humanity. In religions that assumed one all-powerful god, this evil force, or the devil, was still under the control of heaven. The Cathars were among those who gave the devil a more dominant role in human fate.

The belief that the world is evil led to the belief that the evil god is responsible not just for the bad things in the world but also for the world itself. The good god rules in heaven and wishes to have human souls go (or return) there. In that case, everything that has to do with property or procreation is detestable because it just lengthens the time spent away from heaven. This means that truly devout dualists eat nothing that has been produced through sex, not meat, eggs, or milk products. At least one heretic hunter said that one way to spot them was because they were so pale.1

There were many varieties of this two-god belief. Some scholars have tried to trace the Cathars back to the early Gnostic Christians or the Manichians, a late Roman religion that fascinated Saint Augustine for a time.2 But, while some of the beliefs are similar, it’s likely that they were not directly connected.

The religion that became Catharism apparently developed in what is now Bosnia in the mid tenth century and established itself in Bulgaria. The first known preacher of a coherent theology was a Bulgarian priest who named himself Bogomil, which means “worthy of the pity of God.”3 From a sermon we have that was written against them by Cosmos, a tenth-century priest, it seems the Bogomils were one of many groups that wanted to reform the Christian church rather than secede from it. They did not venerate the cross, for why glorify a murder weapon? They pointed out the hypocrisy of many of the church authorities, something that Cosmos was forced to agree with. But he was shocked that they rejected the whole Old Testament and allowed only part of the New Testament.4

Cosmos complained that the Bogomils were falsely religious, that they were humble and fasted just for effect. They carried the Gospels with them but misinterpreted it. One of the worst of these mistakes was that “everything exists by the will of the devil: the sky, sun, stars, air, earth, man, churches, crosses: everything which emanates from God, they ascribe to the devil.”5Finally, these heretics saw no need for priests, confessing instead to each other and forgiving each other.

These two beliefs were what set the dualists apart from other Christians and it was a difference that could not be bridged.

Cathars clearly regarded themselves as good Christians, since that is exactly what they called themselves. On the surface, their basic beliefs seem unremarkable. Most people would have difficulty in distinguishing the principle Cathar beliefs from what are now regarded as conventional orthodox Christian beliefs. However, pursuing their fundamental beliefs to their logical conclusion revealed surprising implications (for example that Roman Catholics were mistakenly following a Satanic god rather than the beneficent god worshipped by the Cathars.)

Like the earliest Christians, Cathars recognised no priesthood. They did however distinguish between ordinary believers (Credentes) and a smaller, inner circle of leaders initiated in secret knowledge, known at the time as boni homines, Bonneshommes or "Goodmen" , now generally referred to as the Elect or as Parfaits.

Cathars had a Church hierarchy and a number of rites and ceremonies. They believed in reincarnation, and in heaven, but not in hell as it is now normally conceived by mainstream Christians.

The Cathar view was that their theology was older than that of the Roman Church and that the Roman Church had corrupted its own scripture, invented new doctrine and abandoned the beliefs and practices of the Early Church. The Catholic view, of course was exactly the opposite, they imagined Catharism to be a badly distorted version of Catholicism. In addition to accusing the Cathars of faulty theology, they imagined a range abominable practices which would have been amusing except that, converted into propaganda, they led to the death of countless thousands through the Cathar Crusades and the Inquisition.

The Roman Church seemed to have successfully extirpated Cathars and Cathar beliefs by the early fourteenth century, but the truth is more complicated. For one thing, modern historians have shown that many Catholic claims were false, while they have vindicated many Cathar claims; and there is a case that the Cathar legacy is more influential today than has been at any time over the last seven hundred years.

Cathars were Dualists. That is, they believed in two universal principles, a good God and a bad God, much like the Jehovah and Satan of mainstream Christianity. As Dualists, they belonged to a tradition that was already ancient in the days of Jesus. (The revered Magi in the nativity story were Zoroastrians - Persian Dualists). Dualism came, and still comes, in many flavours. Even the Cathar variety came in more than one flavour, but the principal one was this: The Good God was the god of all immaterial things (such as light and souls). The bad God was the god of all material things, including the world and everything in it. He had contrived to capture souls and imprison them in human bodies through the process of conception. As Cathars put it, we are all divine sparks, even angels, imprisoned in tunics of flesh.

According to later Cathar ideas, when we die the powers of the air throng around and persecute the newly released soul, which flees into the first lodging of clay that it finds. This "lodging of clay" might be human or animal. The soul would therefore be condemned to a cycle of rebirth, trapped in another physical body. By leading a good enough life human beings or rather their souls could win freedom from imprisonment and return to heaven, the immaterial realm of the good god. For members of the Elect, those who had undertaken the Consolamentum, death was no more than taking off a dirty tunic.

The Cathars were a religious group who appeared in Europe in the eleventh century, their origins something of a mystery though there is reason to believe their ideas came from Persia or the Byzantine Empire, by way of the Balkans and Northern Italy. Records from the Roman Catholic Church mention them under various names and in various places. Catholic theologians debated with themselves for centuries whether Cathars were Christian heretics or whether they were not Christians at all. The question is apparently still open. Roman Catholics still refer to Cathar belief as "the Great Heresy" though the official Catholic position is that Catharism is not Christian at all.

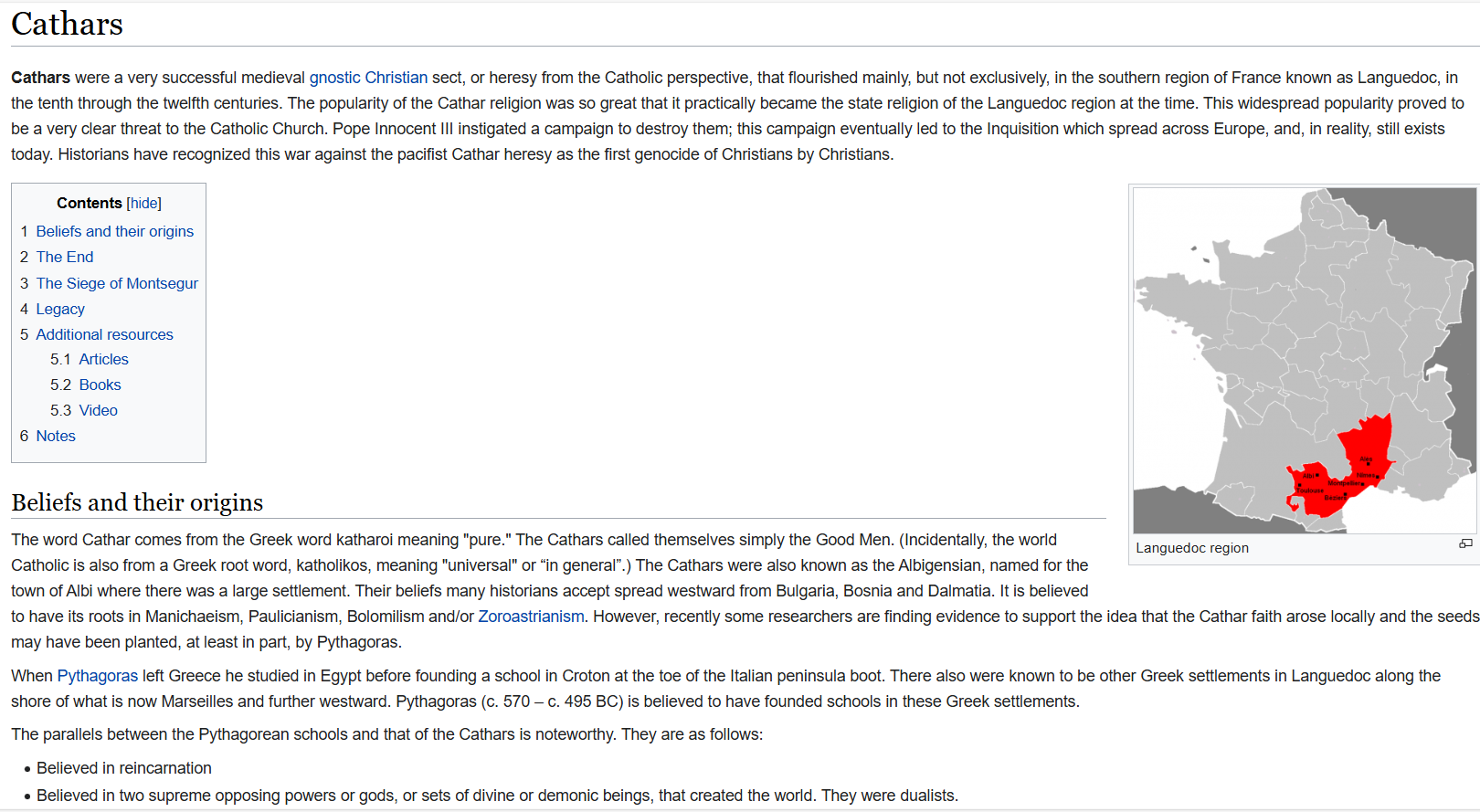

The religion flourished in an area often referred to as the Languedoc, broadly bordered by the Mediterranean Sea, the Pyrenees, and the rivers Garonne, Tarn and Rhône -— and corresponding to the new French region of Occitanie (or the old French regions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées)

As Dualists, Cathars believed in two principles, a good god and his evil adversary (much like God and Satan of mainstream Christianity). The good principle had created everything immaterial (good, permanent, immutable) while the bad principle had created everything material (bad, temporary, perishable). Cathars called themselves simply Christians; their neighbours distinguished them as "Good Christians". The Catholic Church called them Albigenses, or less frequently. Cathars.

Cathars maintained a Church hierarchy and practiced a range of ceremonies, but rejected any idea of priesthood or the use of church buildings. They divided into ordinary believers who led ordinary medieval lives and an inner Elect of Parfaits (men) and Parfaites (women) who led extremely ascetic lives yet still worked for their living - generally in itinerant manual trades like weaving. Cathars believed in reincarnation and refused to eat meat or other animal products. They were strict about biblical injunctions - notably those about living in poverty, not telling lies, not killing and not swearing oaths.

Basic Cathar Tenets led to some surprising logical implications. For example they largely regarded men and women as equals, and had no doctrinal objection to contraception, euthanasia or suicide. In some respects the Cathar and Catholic Churches were polar opposites. For example the Cathar Church taught that all non-procreative sex was better than any procreative sex. The Catholic Church taught - as it still teaches - exactly the opposite. Both positions produced interesting results. Following their tenet, Catholics concluded that masturbation was a far greater sin than rape (as mediaeval penitentials confirm). Following their principles, Cathars could deduce that sexual intercourse between man and wife was more culpable than homosexual sex. (Catholic propaganda on this supposed Cathar proclivity gave us the word bugger, from Bougre, one of the many names for medieval Gnostic Dualists)

In the Languedoc, known at the time for its high culture, tolerance and liberalism, the Cathar religion took root and gained more and more adherents during the twelfth century. By the early thirteenth century Catharism was probably the majority religion in the area. Many Catholic texts refer to the danger of it replacing Catholicism completely.

The cathar castles of southern France are among the most fascinating castles in France, both because of their dramatic locations and the tales of bravery and persecution that surround them.

No visit to the cathar castles would be complete without some knowledge of the cathar religion itself, to better understand the events that unfolded here

Background - cathar religion

The Cathar religion has its roots in eastern religions of 2500 years ago, with the ideas o Zoroastre (Zarathoustra) that the world consisted of two opposing forces, representing good and evil. Many subsequent religions take this starting point, and the Cathar religion that arrive in Europe via the Balkans in the 11th century is one of these.

The fundamental difference between a 'dualist' religion like the cathars, and a religion like Christianity, is the importance given to the evil forces. Cathars and other dualists believe that these are of equal importance, whereas Christians believe that the forces of good are superior.

Although it shares many principles with Christianity, the Cathar religion differs from the Christian religion in some important respects. Marriage was outlawed, as was the private ownership of property. The cathars believed in reincarnation as a path towards eternal life, were strictly vegetarian, and had to abstain from all sexual pleasures. The abstinence from sex was because the cathars believed that a good soul, created by God, was trapped in an evil body, created by the devil. The goal was to reach heaven, not to perpetuate life on an evil earth.

The goal of the cathar religion was to obtain purity, to become 'parfaits'. As with all religions perhaps, the number of truly dedicated, who followed the rules to the letter, was substantially less than the number who broadly supported the principles of the religion but did not forego all earthly pleasures.

The word kathari, from which cathar is probably derived, is the Greek word for pure.

Cathars in France

The Cathars in France were based largely in the Languedoc region, near Toulouse, and Albi and Carcassonne, with a popularity arising at least in part as a reaction to the over-excesses of the Roman Catholic church. The Cathar religion was supported by many in the region, both peasants and nobles alike - perhaps 10% of the population were supporters.

At this stage, the Toulouse Counts owned large parts of the south of France, and were more 'modern' than the northern part of the country, rejecting the feudal structures of northern France. It was also this 'modernism' - for example, cities were allowed to elect their own representatives - that helped allow the Cathar religion to spread.

Initially attempts were made to unite the Cathars and the Catholics, but these were not successful. The Catholic church considered the Cathar religion as heretical, because it rejected significant parts of both the old and New Testaments, including the notion that God created a fundamentally good earth. Cathars attributed the creation of the heavens to God, and the Earth to the devil.

Hence the greater the strength of the cathar religion, the greater the threat perceived by the Catholic church. When Pope Innocent III was elected in 1198 the battle against the Cathars started in earnest, and this conflict between the cathar religion and the catholics would eventually be the downfall of the cathars.

Early in the 1208 a papal legate was murdered by a representative of the Count of Toulouse (quite possibly without his knowledge or support) and this provided a pretext for the Pope to launch a crusade against the Cathars - the Albigensian Crusade - because of the threat the Roman Catholic church believed it poised to their authority. In reality, the Crusade has as much to do with controlling the southern nobles as defeating the Cathars, and it was with the support of the King and northern nobles that the crusade was launched.

Cathars rejected the teachings of the Catholic Church as immoral and most of the books of the Bible as inspired by Satan. They criticized the Church heavily for the hypocrisy, greed, and lechery of its clergy, and the Church’s acquisition of land and wealth. Not surprisingly, the Cathars were condemned as heretical by the Catholic Church and massacred in the Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229 CE) which also devastated the towns, cities, and culture of southern France.

The religion flourished in an area often referred to as the Languedoc, broadly bordered by the Mediterannean Sea, the Pyrenees, and the rivers Garonne, Tarn and Rhône -— and corresponding to the new French region of Occitanie (or the old French regions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées)

The word Cathar comes from the Greek word katharoi meaning "pure." The Cathars called themselves simply the Good Men. (Incidentally, the world Catholic is also from a Greek root word, katholikos, meaning "universal" or “in general”.) The Cathars were also known as the Albigensian, named for the town of Albi where there was a large settlement. Their beliefs many historians accept spread westward from Bulgaria, Bosnia and Dalmatia. It is believed to have its roots in Manichaeism, Paulicianism, Bolomilism and/or Zoroastrianism. However, recently some researchers are finding evidence to support the idea that the Cathar faith arose locally and the seeds may have been planted, at least in part, by Pythagoras.

When Pythagoras left Greece he studied in Egypt before founding a school in Croton at the toe of the Italian peninsula boot. There also were known to be other Greek settlements in Languedoc along the shore of what is now Marseilles and further westward. Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BC) is believed to have founded schools in these Greek settlements.

The parallels between the Pythagorean schools and that of the Cathars is noteworthy. They are as follows:

- Believed in reincarnation

- Believed in two supreme opposing powers or gods, or sets of divine or demonic beings, that created the world. They were dualists.

- Teachings were orally transmitted – it was forbidden to write them down

- Accepted both men and women equally into their ranks - gender was not a barrier to rising in the ranks

- Had an inner and outer circle of believers – the inner circle was held to much stricter standards of behavior than the outer circle of the believers known as croyants (believers). The inner circle was privy to the higher secrets unavailable to the outer circle of followers.

- Personal property of all kinds was relinquished to the church. This was expected of the inner circle but not the outer circle.

Cathars did believe in the teachings of Jesus in their purest form, which they felt had been corrupted by the Catholic Church. They did not recognize the authority of the Pope but maintained their own loose structure of a church with bishops at varies levels and overseeing different territories. As an oral tradition, the Cathars had few written books they considered sacred but there were a few- besides the New Testament, The Gospel of the Secret Supper, or John's Interrogation and The Book of the Two Principles. There has been confusion concerning Cathar attitude toward John the Evangelist and John the Baptist. Strangely Cathars did not look favorably upon John the Baptist, describing him as a "demon."[1] They believed Jesus passed on his secret teachings to his inner circle which included young Saint John.

Cathars found the Catholic practice of worshipping a crucifix, an effigy of their savior dying of a cross, abhorrent. In fact, some Cathars believed Jesus was never crucified or that he had survived the crucifixion and had come to southern France to escape further persecution. Why France? It has been suggested that during the so-called “lost years” of Jesus he spent his time in Egypt (just at Pythagoras did) learning the esoteric secrets he revealed to his inner circle and preached in his ministry.

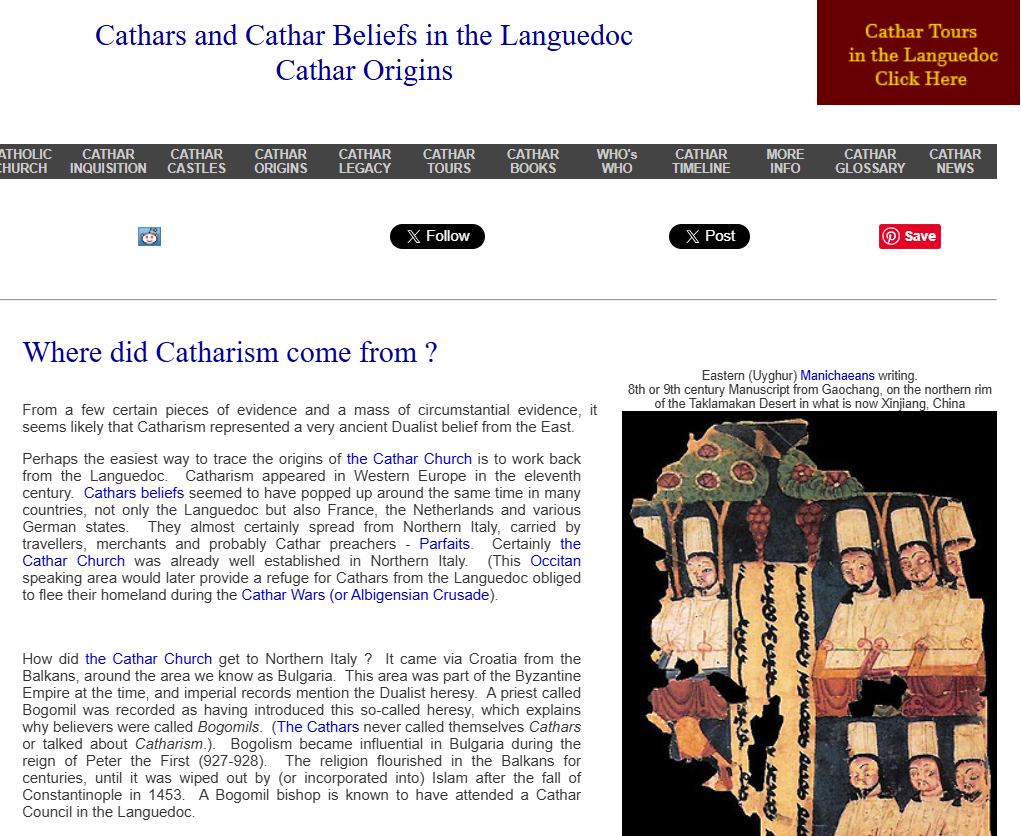

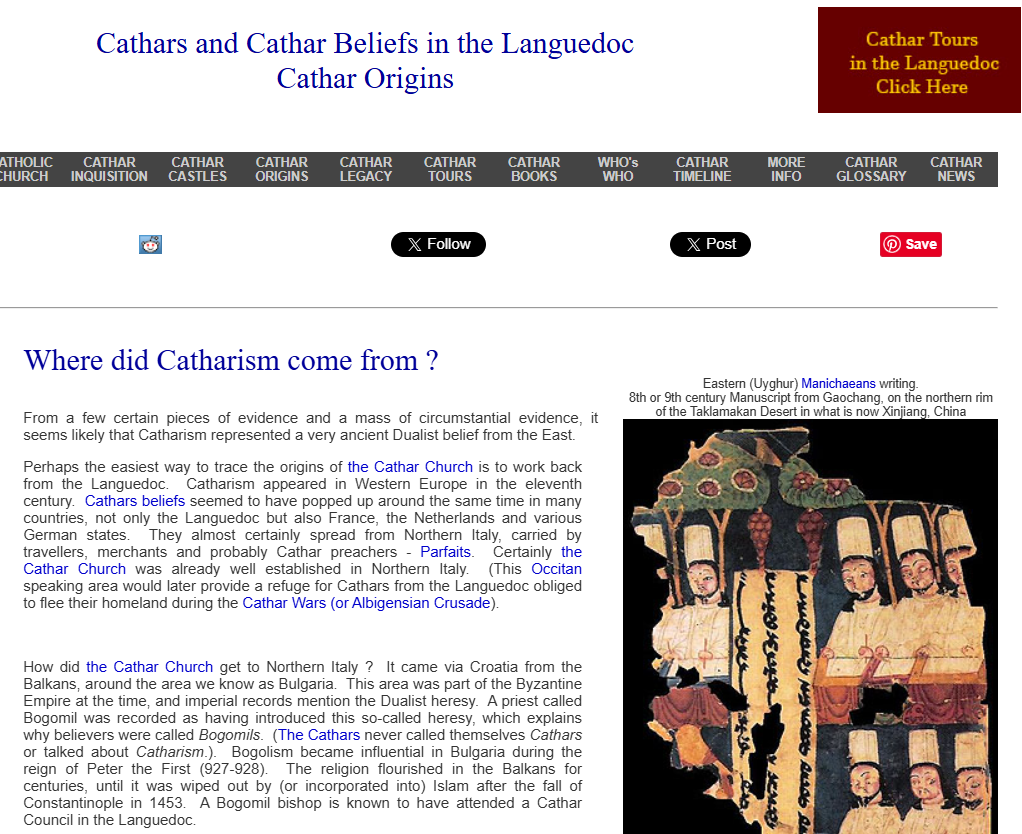

From a few certain pieces of evidence and a mass of circumstantial evidence, it seems likely that Catharism represented a very ancient Dualist belief from the East.

Perhaps the easiest way to trace the origins of the Cathar Church is to work back from the Languedoc. Catharism appeared in Western Europe in the eleventh century. Cathars beliefs seemed to have popped up around the same time in many countries, not only the Languedoc but also France, the Netherlands and various German states. They almost certainly spread from Northern Italy, carried by travellers, merchants and probably Cathar preachers - Parfaits. Certainly the Cathar Church was already well established in Northern Italy. (This Occitan speaking area would later provide a refuge for Cathars from the Languedoc obliged to flee their homeland during the Cathar Wars (or Albigensian Crusade).

How did the Cathar Church get to Northern Italy ? It came via Croatia from the Balkans, around the area we know as Bulgaria. This area was part of the Byzantine Empire at the time, and imperial records mention the Dualist heresy. A priest called Bogomil was recorded as having introduced this so-called heresy, which explains why believers were called Bogomils. (The Cathars never called themselves Cathars or talked about Catharism.). Bogolism became influential in Bulgaria during the reign of Peter the First (927-928). The religion flourished in the Balkans for centuries, until it was wiped out by (or incorporated into) Islam after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. A Bogomil bishop is known to have attended a Cathar Council in the Languedoc.

The next question is how the religion got to Bulgaria. The answer is that it probably spread from the Eastern Part of the Byzantine Empire to the Western Part. It may have originated in a form of Manichaen belief, itself a melange of Persian Zoroastrianism and early Christian Gnostic Dualism, but it is more likely that it represented a separate strand of early Christian Gnostic Dualism. Early Christianity possessed three main strands: the Jewish one (led by James, Jesus' brother), the Pauline one (created by Paul himself and now represented by the Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches), and the Gnostic one (at least some of whom followed St John, the disciple). It is well within the bounds of possibility that Catharism represented this early tradition. Certainly the Cathars favoured the John Gospel over all other scripture.

The Catholic Church for a long time regarded Cathars as neo-Manichaeans, but they were almost certainly wrong (as the Catholic Encyclopedia now recognises), since the Cathars shared only Gnostic Dualist ideas - not any of the distinctive Manichaen ideas. (Even so one of the leading scholarly books on the Cathars (by Sir Steven Runciman, published in 1982) recording translations of primary records is entitled "The Medival Manichee"

The Cathars were by no means the first dualistic, ascetic Christian sect to occur during the medieval period. The origins of their beliefs are generally thought to have originated further east, in the Byzantine Empire. It is likely that these religious ideas that influenced Catharism reached France along trade routes that passed through Bulgaria on their way from Byzantium.

The Bogomils in particular have been identified as being very similar in doctrine to the Cathars. Originating in the teachings of the Bulgarian priest Bogomil, who was active during the 10th century in the First Bulgarian Empire, the Bogomils rejected the church and secular hierarchy in favor of personal faith and religious knowledge. Crucially, like the Cathars they were also dualists and did not even believe in building churches – instead, they believed that the body itself was sacred, and purified it through fasting, purging and dancing.

The earlier Christian sect known as the Paulicians may have been the origin of Cathar belief, as they almost certainly influenced the Bogomils themselves. Emerging in Anatolia in the 7th century, the Paulicians may also have been dualists and were almost certainly adoptionists (believing that Christ was not born son of God, but was ‘adopted’). Like the Cathars, the Paulicians were subject to repression and persecution by the Byzantine state.

Aspiring modern Cathars look back to the myths of the original spiritual realm, the fall of Satan and the angels, and the creation of the material world in which souls reincarnate until they can escape. They also look back to the historical groups and individuals who were involved with the development of this worldview in the first place. Modern esoteric lineages typically derive not from antiquity but from revivals that occurred in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Thus when exploring movements like the Gnostics of antiquity or the Cathars of the Middle Ages, the modern spiritual seeker is often presented with a melange of spiritually-unsympathetic popular history, obtuse scholarly research, and a revivalist esoteric tradition that often has little to do with critical history.

The Cathars are best known not for what they did but for what was done to them. The Albigensian Crusade, launched in 1209 on the authority of Pope Innocent III, laid waste to the Languedoc in the south of France. The Inquisition was subsequently founded to root out and eradicate what remained of the Cathar heresy. Books on the Cathars focus on the relentless march of the crusading army as it moves from castle to castle, siege to siege, atrocity to atrocity. Or historians weigh up the influence of the Inquisition, a ruthless bureaucracy that survived into the nineteenth century. Tourists visit the Languedoc, now branded as Cathar country, for the fairytale citadel of Carcassonne, restored in the nineteenth century, for the wild ruins of medieval castles on challenging hilltops, and for the relaxed locals, good weather, cheap food and wine.

How did the Cathar Church get to Northern Italy ? It came via Croatia from the Balkans, around the area we know as Bulgaria. This area was part of the Byzantine Empire at the time, and imperial records mention the Dualist heresy. A priest called Bogomil was recorded as having introduced this so-called heresy, which explains why believers were called Bogomils. (The Cathars never called themselves Cathars or talked about Catharism.). Bogolism became influential in Bulgaria during the reign of Peter the First (927-928). The religion flourished in the Balkans for centuries, until it was wiped out by (or incorporated into) Islam after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. A Bogomil bishop is known to have attended a Cathar Council in the Languedoc.

The next question is how the religion got to Bulgaria. The answer is that it probably spread from the Eastern Part of the Byzantine Empire to the Western Part. It may have originated in a form of Manichaen belief, itself a melange of Persian Zoroastrianism and early Christian Gnostic Dualism, but it is more likely that it represented a separate strand of early Christian Gnostic Dualism. Early Christianity possessed three main strands: the Jewish one (led by James, Jesus' brother), the Pauline one (created by Paul himself and now represented by the Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches), and the Gnostic one (at least some of whom followed St John, the disciple). It is well within the bounds of possibility that Catharism represented this early tradition. Certainly the Cathars favoured the John Gospel over all other scripture.

The Catholic Church for a long time regarded Cathars as neo-Manichaeans, but they were almost certainly wrong (as the Catholic Encyclopedia now recognises), since the Cathars shared only Gnostic Dualist ideas - not any of the distinctive Manichaen ideas. (Even so one of the leading scholarly books on the Cathars (by Sir Steven Runciman, published in 1982) recording translations of primary records is entitled "The Medival Manichee")

The eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries were marked by resurgence in Europe of spiritual movements of clearly Gnostic character. During the late eleventh century a Gnostic religion that had survived orthodox persecution for many centuries in the Byzantine Empire and on the Balkan Peninsula – the Bogomil religion – found its way to the Languedoc region of Southern France and to areas of Northern Italy. There it took root and flourished over the next three centuries as the Cathar religion -- the tradition of the Good and True Christians, the Bons Hommes. (The term "Cathar" was used in medieval times in a derogatory fashion by opponents of the Bons Hommes; Cathars simply called themselves "Good Christians.")

During these same centuries in the area around the Southern Pyrenees a form of heterodox mysticism took hold, a mysticism that had historical and archetypal roots in the Gnosis and Gnosticism of late antiquity. At precisely this time, and in the same area of Southern France, there came the first flowering of the Troubadour traditions and of the Jewish Gnosticism of Kabbalah. To the south in Spain, the mystical tradition that gave root to a Gnostic school in Islam took form – exemplified by Ibn 'Arabī (1165–1240), the seminal figure in Turkish, Persian and Sufi Gnostic traditions. St. Francis of Assisi (1181–1226) was also deeply influenced by the spirit of this time and this Cathar land.

The relation of the Bons Hommes with this heterodox flowering of Christian, Jewish and Islamic mystical traditions has long fascinated historians. There is no verifiable answer to the relationship of these several movements, but the milieu in which they arose represents an obvious resurgence of Gnostic tradition: a spirit of Gnosis animated this time and region.

Unfortunately, the Crusade against the Cathars in the thirteenth century effectively eradicated the tradition and destroyed most of its primary documentary history. Only a few original Cathar texts are preserved. Among the most important surviving writing are a Gospel text from the tradition of John and an authentic liturgical text known as the Cathar Ritual. (Two manuscripts of the Cathar Ritual survive, one in Latin and one in Occitan; the version in Occitan is often referred to as the "Lyon Ritual"). The longest surviving Cathar text is the Book of the Two Principles, a sophisticated and persuasive critique of orthodox theology. We provide all three of these texts below.

Not everyone is aware that the Scriptures have several meanings representing various levels of thought. The historical material sense corresponds to a spiritual non-temporal meaning, and the Gnosis is only concerned with the latter. That is, the texts which follow are, of course, taken exclusively in the spiritual sense.